Long before he won the National Book Award, Martín Espada worked after school in a factory making legal pads. Espada, retired U.S. Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer, economists Natasha Sarin, Betsey Stevenson, and Justin Wolfers, historian Jill Lepore, and actor John Turturro join Elisa New to reflect on social mobility, and what connects manual labor with the raw materials of poetry and law.

Interested in learning more? Poetry in America offers a wide range of courses, all dedicated to bringing poetry into classrooms and living rooms around the world.

By Martín Espada

At sixteen, I worked after high school hours

at a printing plant

that manufactured legal pads:

Yellow paper

stacked seven feet high

and leaning

as I slipped cardboard

between the pages,

then brushed red glue

up and down the stack.

No gloves: fingertips required

for the perfection of paper,

smoothing the exact rectangle.

Sluggish by 9 PM, the hands

would slide along suddenly sharp paper,

and gather slits thinner than the crevices

of the skin, hidden.

Then the glue would sting,

hands oozing

till both palms burned

at the punchclock.

Ten years later, in law school,

I knew that every legal pad

was glued with the sting of hidden cuts,

that every open lawbook

was a pair of hands

upturned and burning.

At sixteen, I worked after high school hours

at a printing plant

that manufactured legal pads:

Yellow paper

stacked seven feet high

and leaning

as I slipped cardboard

between the pages,

then brushed red glue

up and down the stack.

No gloves: fingertips required

for the perfection of paper,

smoothing the exact rectangle.

Sluggish by 9 PM, the hands

would slide along suddenly sharp paper,

and gather slits thinner than the crevices

of the skin, hidden.

Then the glue would sting,

hands oozing

till both palms burned

at the punchclock.

Ten years later, in law school,

I knew that every legal pad

was glued with the sting of hidden cuts,

that every open lawbook

was a pair of hands

upturned and burning.

© Martín Espada, 1993; used by permission of author.

“I was 16 years old, I needed a job, and that turned out to be working in a printing plant. I learned how to make legal pads. It was not at all what I expected,” says National Book Award winner, poet Martín Espada about the after-school job which inspired his poem. His later experience, studying to be a housing rights lawyer, inspired it too. “When I got to law school, I noticed that I was surrounded, as if in a nightmare, by a sea of legal pads. And I was surrounded too by people who had absolutely no idea how they were made.” Pictured above is the poet as a young man, courtesy of Frank Espada Photography.

“Part of doing anything manually, you're going to cut your hands. But they don't tell you that. No one tells you that.” - Emmy Award winner, John Turturro

Former law student James "Jimmy" Biblarz reflects on the multiple meanings of the word "hidden" in the line "I knew that every legal pad / was glued with a sting of hidden cuts.” He notes, "I see hidden there as connecting to you want to keep your past hidden at law school. You may not want disclose that you have this manufacturing past at a place where prestige and background are so essential." Image Credit: Kheel Center, Cornell University Library

“The legal pad does have a special advantage: Its large size. If you have an 8 by 11, you run out of paper because you might have a better idea. By the time you get to the bottom three inches, you might, there's always that hope,” says retired Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer.

As historian Jill Lepore says: “There's a long literary tradition in American letters of evoking the paper mill.” Including, as noted in the episode, Herman Melville's short story "The Paradise of the Bacherlors and the Tartarus of the Maids"—inspired by his 1851 trip to Carson's Old Red Paper Mill in Dalton, Massachusetts. For both Melville and Espada, paper making makes for a fruitful parallel to the writing process. Espada's poem, although ostensibly about his law school classmates, also points towards his peers in poetry: Are there parallel grisly stories behind their preferred stationery? Is someone burning for the perfection of their paper?

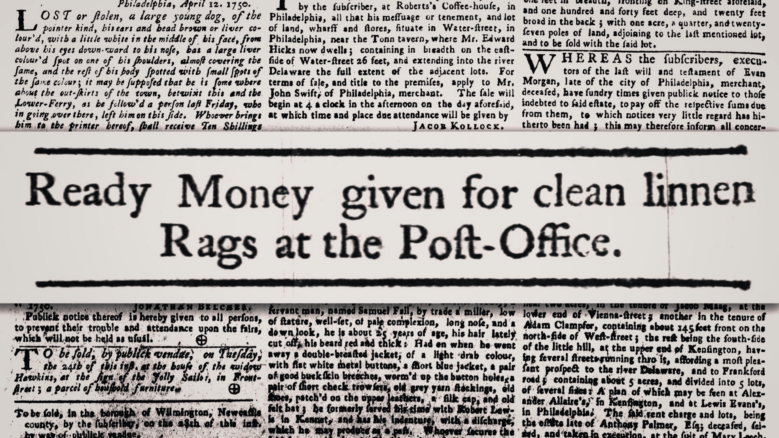

There is, of course, another famous connection between paper and American upward mobility: the classic tale of rags to riches, which to paper making, can apply literally. Professor Lepore notes, “Benjamin Franklin printed paper made out of rags. That's rags to riches.” An unease with class advancement is lurking behind Espada’s poem too—when you start doing the writing, can you really forget how the paper is made? In the above image, we see Franklin’s newspaper, "The Pennsylvania Gazette," putting out a request for rags.